We were in Washington DC, in the final few days that DC existed, for the Twenty-Seventh Annual Mid-Atlantic Regional DiscDog Invitational. I was there with Daisy, my Aussie-mix, and my pal Penny, whose Border Collie was also named Penni, but with an I at the end. Penni-with-an-I was a favorite to win the whole thing. My Daisy was just good enough to keep getting invited to competitions.

A week of storms had muddied the grass on the National Mall. Our dogs tore up clumps of turf with every leap. I pitied whoever was going to have to restore the surface after we left. Gray-white monuments blurred into the clouds, a city half disappeared. Lines of tourists stood at hot dog carts.

Daisy had already made her run first thing in the morning, and we’d done okay, nailing a couple of the tougher moves we often muffed. Now we watched from the sidelines. My shoes, soaked through, squelched as I shifted my weight in the muck.

On the field, Penni-with-an-I snagged each catch with a surgical nip. I swear she could strike a pose at the peak of a leap. If the DiscDog Tour were ever to adopt a new logo, her silhouette would be it. A random crowd of tourists had gathered. Usually it was just the other competitors watching, but even these amateurs recognized excellence. When Penny and Penni-with-an-I finished their routine, an honest-to-god roar of applause broke out.

At the closing ceremony, it was no surprise when Penni-with-an-I claimed the title, her fifth so far that season. The winnings, though slim, would more than cover the cost of our motel. I’d trained Daisy to make a clapping motion with her front paws, so she mimed along as the trophies were bestowed. Penny accepted a comically tall trophy, human height, a lacquer that failed to disguise the tin underneath. I wasn’t sure the trophy would fit in the minivan with the rest of our stuff.

James Ensor, a purebred Aussie, had come in second, trained by Reggie. Reggie was barely past drinking age, but he’d been on tour since his teens, so we all cared for him like a kid brother. He ran a solid business training other people to train their dogs. He drove the newest minivan out of anyone at the competition.

After the awards, we mingled for a while with the judges and other competitors, chatting as if we hadn’t seen them just the week before at another competition and also the week before that.

Natalie, who we sometimes joked dressed more like a horse girl than a dog trainer, led over her Jack Russell, Swifty. Nat had married into money, but before that she sometimes stayed in motels with us, sharing a bed with Penny. That meant all three dogs would curl up on the other side of my bed. Daisy scampered over to Nat and bowed her head for pets. Swifty tapped his front paws in place, a happy little dance.

The gathering thinned. The judges disassembled the podium. Daisy nipped my pants leg and tugged. Time to go.

I gave Penny a side hug on the walk to the van.

“Congrats,” I said.

“Wasn’t me,” she said.

As if Penni-with-an-I could have thrown and caught the frisbee both.

I strapped the trophy to the luggage rack. We drove to Alexandria for a late lunch and walked the dogs around Old Town, row houses and posh shops. On the drive out to I-95 and eventually New York, we noted the cars streaming into the parking lots at the Pentagon. The dogs bristled, pacing the back seat until the building was out of sight.

* * *

That night we splurged and got a decent hotel in Manhattan. It was the national championships, after all. Since we always shared a room on tour, a woman and a man, both suburban thirty-somethings, most people assumed Penny and I were a couple. But we’d vowed to never sleep together. Close friends, only, we’d decided made the most sense. Two queen beds in every room.

Penny stirred all night. Was it the bustle of the city or nerves before the biggest event of her dog-training life? I could’ve asked her, but I feigned sleep. What comfort could I offer? In the morning, Penny took twice as long as normal in the shower. Penni-with-an-I almost had to push her out the door.

The National DiscDog Championships were in Central Park, using the softball fields near the carousel. Penny and I had both gotten draws later in the day, so all we had to do in the morning was watch.

We didn’t realize it yet that our hotel, along with the entire south end of Manhattan, had already been zapped to nothingness. Not to mention DC and Philly, too.

Wally Beatty, a perpetually stoned guy who lived fulltime in the half-sized RV he drove to competitions, was up in the MicroDog competition with his Yorkie, Galactus. Beatty was a goof, but a solid trainer. He’d win a lot more often if he spent any time at all practicing with the disc himself. He can pitch a decent backhand—who can’t?—but the rest of his throws almost always leave Galactus scrambling. That’s the opposite of me. I can throw a disc all day, but I lack the patience to train Daisy the hours required for her to be a top-notch competitor. We have a good time, though, and we do well enough.

Beyond the end of the park, a neon glow grew in the sky. Electric sizzles started faint and amplified, bursts of purple light, then the new Central Park Tower flickered like a character getting electrocuted in a cartoon, the steel beams inside an x-rayed skeleton, and the building was gone. No tumble, no rubble, no smoke.

All the dogs made agitated laps around their trainers’ feet. Dogs that never growled, growled.

The growls and the sizzles were the only sounds. The relative quiet upset my expectations for a disaster. Action movies had prepared me for explosions, panicked masses. This was something different. I simply watched, as if no noise meant no threat. As if I couldn’t possibly be on hand to witness the end of the world.

Beatty was so focused on his routine that he failed to notice the disappearing buildings. Galactus, at least, snatched glances between tricks and emitted worried yips, but he kept his head in the game. The judges, too, the same three from the previous competition, stayed intent on their duties, ignorant to the distance. The crowd on the other side of the field from us, facing away from the city, cheered a leap by Galactus.

From behind where the buildings had been, the sky churned. I thought it was a host of sparrows, but the motions were too angular. Not a single swoop. A small group of the dots headed toward the park while the rest split off to either side. More buildings flashed and vanished. Car tires screeched and horns honked. Then…nothing.

Penny grabbed my shoulder. Her touch made the absurdity real.

“What should we do?” I asked.

“What do you do in the face of that?” She swept her free hand to indicate the swarming sky.

Panic erupted at the end of the park. The little hovering dots pelted the earth with purple rays. Where the rays found people, the people disappeared. One shrill scream finally caught Beatty’s attention and he glanced up. Galactus, running full speed for a trick, jumped right into his face. Blood poured from Beatty’s nostrils. Galactus seemed unfazed.

The dots in the sky were close enough now to have shapes. Flying saucers, obvious to anyone who’s ever watched a science fiction flick, thin and spinning and unearthly silver. But something was off. The depth was wrong, the saucers too close. They were far smaller than the old movies had predicted. These were no more than hubcaps or plates or, dare I say it, frisbees.

The judges were the first of our friends to die. Atop a dais, surrounded by a snare of audio cables and power cords, they were nothing if not targets. Penny’s hand slipped from my shoulder. The judges had all been good, dog-loving people. I thought of their own poor dogs at home, and how the dogs would wait and wait and never stop waiting.

These same three judges had served at competitions around the country. Their notes, given in scribbled scrawl after the awards had been presented, always cited my hesitancy. After one competition, the judges approached me as one, a three-faced tribunal, and observed that all my commands emerged like apologies. I’d scoffed then, but they were right, of course. I apologized now under my breath.

Penny pulled me by the arm to the cover of a tree and whistled for Daisy and Penni-with-an-I to follow. The saucers didn’t seem to be attacking people under trees. Could it be a faulty sensor? Did the saucers see people near trees as part of the trees themselves?

From there, I watched the attack, witnessed more victims vanish. The cleanness of their deaths, the quickness of their disappearance, the iota before they were gone when I could literally see the insides of them flash translucent, bones and organs, this all made me more curious than sad. Sadness would come later. But I saw something else, too. The saucers targeted our dogs as often as people, but those shots never found their mark. The dogs scampered in random patterns that flummoxed the saucers’ aim. I thought back to the people who had been killed as they ran away. All of them had fled in slow, straight lines.

I stepped from under the tree and shouted, “Don’t run straight! Bob and weave! Get to a tree if you can!”

Not everyone heard me, and not everyone heeded what I’d said. But those who did started surviving. They ran in zig-zags alongside the dogs as the death rays left singed polka dots in the grass around them. More and more people pressed their backs to the trunks of trees.

Years before, after another competition, Penny and I had taken the dogs to a park on the marshy shore of a Georgia barrier island. We found a whole tree washed up in the mud, the driftwood surface marbled and smooth. We crawled among the bare, crooked branches, posing for selfies. We climbed onto the trunk and leaned into each other, watching the dogs romp through the mud, chasing fiddler crabs. I remember feeling warm and safe, but also scared of the feeling. I pulled away from Penny and hopped off the tree and joined the dogs. There are still stains on the backseat of Penny’s van from the mud we tracked back in.

A saucer zipped toward me, buzzing like a broken oboe. I dove to the side just in time, a death ray landing where I’d been, the air suddenly hot and dry, tinged with a scent like fresh popcorn. I scrambled back under the tree. Beatty and Galactus had joined us, three people, three dogs. The saucer jerked to a stop, only a slight waver to show that time hadn’t stopped with it.

How long could it wait? Versus how long could we wait? Beatty’s nose had stopped bleeding, but a burgundy stain fanned down the front of his T-shirt. He looked woozy, though to be fair he was always a little bit out of it. Penny crouched by Penni-with-an-I’s side. Our dogs whimpered.

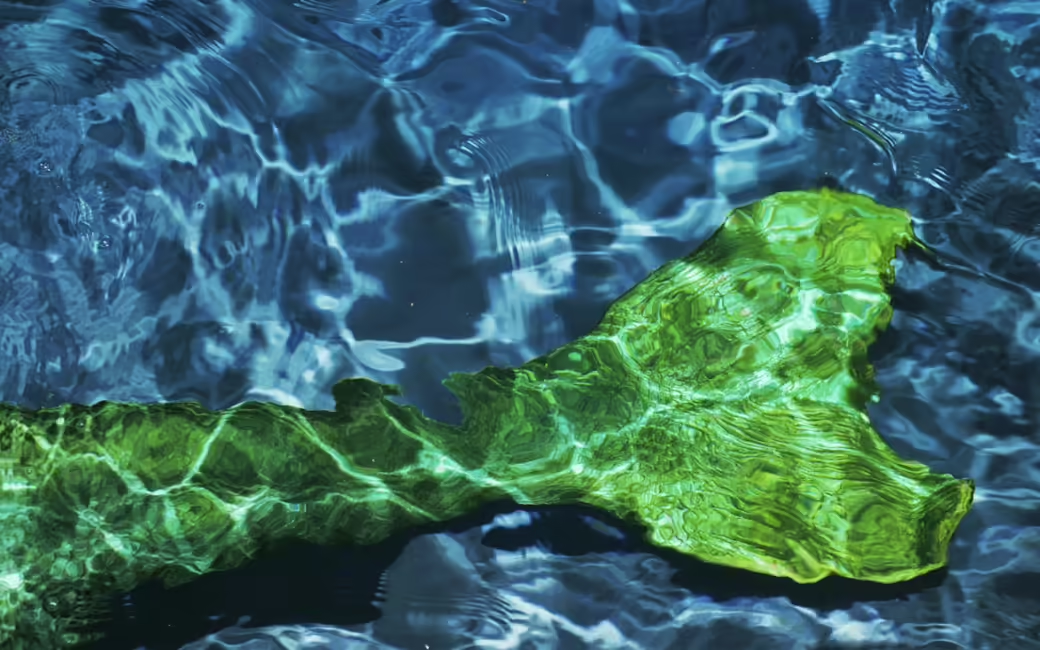

I reached into my backpack and drew out a frisbee. It was Daisy’s favorite, a vibrant purple, brighter even than the death rays that still fell throughout the park and obliterated the buildings of Manhattan around us. I didn’t think about what I was doing. I simply followed the instinct that told me to make my dog happy when she was sad.

I gripped the disc, too tightly for good form, but my backhand flew quick and true, and it hit the hovering saucer square.

The saucer sputtered in place and began to descend. Such a tiny thing, really. Lower and lower. Daisy dashed out. I called after her to stay, but she didn’t listen, the only time she’d ever ignored a command since she was a puppy. She leapt and chomped the saucer and landed and shook her head side to side. The saucer sparked from the holes her teeth had made. She yipped and dropped it. The saucer didn’t rise again.

All around us, the other saucers stopped, too, dangling like ornaments in the sky. The weird buzzing faded.

Saucers that had been attacking the city proper pincered in from either side of the park. Their motion was slower than before, hesitant, but their flight triggered a new sense of unease. You throw enough frisbees and you come to recognize how a disc flies, even when that disc is a spaceship and moves like nothing you’ve ever seen before. Or maybe I just sensed the danger to Daisy. She was the epicenter of the saucers’ approach. She was the threat the aliens had identified.

I stepped from the tree again and called out, “Your discs! Use every disc you’ve got!”

Others repeated my command, the order passing from tree to tree. Seeing a little dog in danger, my sweet, sweet Daisy, chased away our fear. There were a thousand saucers, at least. Far fewer of us. But we had something no alien could ever hope to understand. We had something dear to protect.

The first wave of saucers arrived, and we met them with discs of our own. The saucers moved too rigidly, too predictably. We knocked them from the sky, one after the other. Our dogs darted forward and finished the job. Then the next wave, and the next. The air resounded with zaps and growls. The snapping shut of jaws.

Penny moved deeper into the field, far from the safety of the trees. She made a quick hand gesture and fell to her hands and knees. Penni-with-an-I jumped onto her back and sprung into the sky, a stunning arc, the kind of jump that won her competition after competition, peaking at the height of a saucer. Penni-with-an-I landed and slung the defeated saucer aside.

Beatty had lost a shoe somewhere along the way. He loped around, retrieving discs and giving them to trainers who could throw better than him.

Little Galactus had gotten one of the saucers in his mouth, but the saucer still managed to fly, spinning Galactus like the blade of a lopsided ceiling fan. The saucer swerved side to side before finally pitching slantwise and sinking to the turf, defeated. Galactus scampered away.

I’d like to say there was no more sadness, but we lost friends. Nat was the first trainer who fell. Swifty sprinted through the field searching for her, his barks turning frantic.

Reggie was surrounded by three saucers and couldn’t escape. His beloved dog, always-cheerful James Ensor, howled, channeling every wolf ancestor for a thousand generations. The rest of our dogs howled in unison, a sound that seemed to come from above, a divine decree. For the first time since we destroyed the first saucer, the aliens hesitated. The little ships quivered in place. Our dogs didn’t wait for the saucers to start moving again.

The bigger dogs, the leapers, surged forward and claimed saucers from the sky. Smaller dogs darted onto the battlefield to retrieve discs for trainers, and eventually started bringing back felled saucers, too, which flew almost as well. We launched volley after volley as fast as we could throw them. More friends gone. Silas, Miranda, Ahmed. An echo of their dogs’ whimpers still sometimes wakes me in the night.

I’d been on the competition circuit for several years when my first dog, Doxy, died. She went into the vet for a simple surgery but had a stroke during the operation. She woke up, but her mind was gone. She spent her last day keening. I never knew sadness had a sound before that.

But here it was again.

Daisy dashed about so quickly amid the ruckus that I sometimes lost sight of her. In those moments dread welled up inside me, but then her tail would fan into view, a proud banner. She was fierce and beautiful and striving.

Penny, too, operated from the center of the fray. She aided other trainers. She urged dogs to safer positions. She directed barrages, wiping clear whole swathes of sky. A general among dog trainers.

Penny had been there when the vet put Doxy to sleep. She was there for the lonely six months when for the first time as an adult I didn’t have a dog in the house. She was there when I went to the pet rescue. Penny was the one who pointed out the shy little mutt puppy and recognized the intelligent depth in Daisy’s eyes. When the kennel door opened, Daisy ran to Penny first, but Penny gestured to me, and Daisy came right over. That was the second hardest I ever cried, second only to the day Doxy died. Once for losing love, once for re-finding it.

The remaining saucers regrouped into a phalanx for a last assault. They descended straight from above. Our discs rose up to meet them. Our dogs followed right behind. Sparks showered down, a weeping willow of light. Only a dozen saucers remained. Then five. Then one.

To that final alien’s credit, they stayed to fight even after their comrades had been decimated. If aliens have a concept of bravery, this was it. But bravery makes fools of any species, from any planet. This fool had one final mistake left to make.

The saucer targeted Daisy, diving at her, firing a continuous death ray in her direction, scorching a line in the grass. Maybe not bravery, then, but vengeance, targeting the first earthling who dared to resist. A scream ravaged my throat, and I ran for my little dog, my best friend. Penny was at my side, the other trainers behind us. But it was over before we got close.

Daisy sidestepped the attack and then leapt, higher than I’d ever seen, a single leap that would have won her this or any competition. She seized the saucer, alighting with perfect grace. I wished the judges had still been alive to score her.

“Leave it!” I shouted at Daisy. It was too harsh a command. I never scolded her. But she looked at me, and I swear she nodded. She got it, even as Beatty came over and asked me what the hell I was thinking.

“Let the saucer go back to wherever it came from,” I said. “Let the aliens know that Earth has an army bred for ten-thousand years just to defeat them. Let them know to fear us. They won’t come back again.”

I crouched beside Daisy and petted her, deep emotion welling up, pride and love and exhaustion all swirled together. “Good girl,” I said. “Good girl.”

She released the little saucer with an upward flip of her snout. The saucer sputtered higher and higher into the sky. It aimed for a small cloud and passed through. A burst of chartreuse light and the cloud dispersed in an instant. A glowing streak trailed away from where the saucer had been.

A teenager came up next to me, dressed in black, thick eyeliner smeared around her eyes, not one of the trainers, just a random person from the park, a local. She held up a middle finger in the direction of the saucer’s wake. I joined her in the gesture, and then Penny and Beatty, and then all the trainers and other survivors. We stood there, sweaty and panting and flipping off the sky. Our dogs stood with us.

A photographer who’d been covering the competition snapped a photo of the scene and a close-up of Daisy. Those two photos would run on the front page of every newspaper in the world, the top of every news website. Daisy would gain fifty million Instagram followers before the next morning.

I took Penny’s hand, lacing my fingers through hers. Daisy nuzzled at my leg. I felt something light in my chest, a sensation I still feel whenever I see an empty sky.

The photographer came up and asked my dog’s name. I told him.

“Daisy,” he said. “Yeah, Daisy.”

My name was never mentioned, just another face among all those in the park. But that’s the life of a trainer, isn’t it? Or a parent or an artist. The thing we create more famous than the creator. The thing we create proof that we acted and it mattered.

Today, in that spot where we all once shared a one-fingered salute, at the edge of the softball fields, there’s a statue, huger than life, metal gleaming, erected even before the rebuilding of Manhattan could begin. It’s a decent likeness of Daisy, proudly mid-leap, reaching for a suspended disc, maybe a frisbee, maybe a saucer. The plaque at the base bears her name and an inscription: “Many were lost, but many more were saved, thanks to a very good dog.”