Bad Boundaries

When I was younger, I hunted men who yearned for deep bar conversations. My habit: find a topic, probe, then sink together into the underworld, both of us a burning mess. “People drink each other like medicine but don’t stop after one sip,” I once said to an open faced man across the table. His amber eyebrows furrowed, I twirled my hair with a sigh, eyeing his throat. When he asked what I meant I startled him with a troubling story (my older, alcoholic roommate’s demand for late night eggs when he stumbled into my room ravenous, and my compliance). When he voiced concern for my safety I dangled karma over his head. He could be us. Who will make us eggs when we’re old and sad and lonely? The light in his eyes grew dark with uncertainty. With practice, dragging them under became second nature. “You bring out the lost soul in me,” one young man quaked, dim light and Kalamata olives between us. We established no safe words. Capturing credulous men built my confidence. Their perplexed faces satisfied my impulse to disrupt instead of soothe.

I experienced a type of hangover after these underworld journeys: a constant queasiness from too much intimacy too fast. I liked it, the junkie’s thrill that resembled the bends. It was easy to ignore their trace resistance, my imperceptible shift away from passion, towards sport.

But once I almost drowned a new acquaintance, crossed a line we both noticed when I mentioned I had convinced a date he was deathly ill because, “he wanted to believe it.” He called me a name I won’t repeat. I resisted the urge to capture earnest company after, despite their complicity. I tried to imagine the feeling, wondering if vampires drew the life out of people like this. Later, I learned my behavior was more like an etheric possession. Not merely a blood draw but a full abduction.

I learned when a colleague tried the same on me. He bought me a drink or two, insisting. I agreed because it was late, and because the bar’s dim mahogany glow surrounded us. I sipped while he monologued about childhood abandonment and romantic rejection, linking the two and throwing them at me like an anchor overboard. I knew the game, how to resist, how to feign growing closer. He was an amateur, unstable and flailing in choppy water.

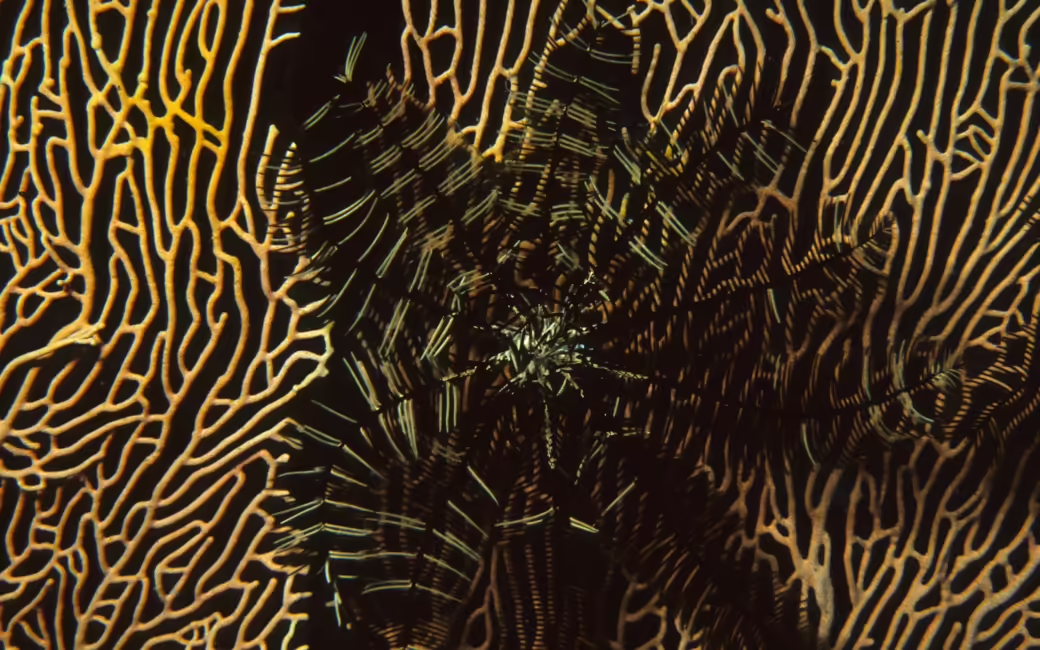

Then, in a terrible shift, he began to cry and I lost track, got pulled under by his sadness. To restabilize I tried to meet him in the depths by admitting some limitation—that my outer membrane was a sponge, more permeable than most —and like an oil spill, he oozed over me until I couldn’t move. Stuck in my seat, I saw something akin to a hand—clear and yellow— reach between our barstools with long fingers and pass through my skin into my viscera. I caught his eye, mid-ramble, to let him know I could feel his violation. Coldness invaded the juncture between my lumbar and thoracic vertebrae, a steel hook into a fish. He did not blink.

Get your phantom hand out of my solar plexus, I said without words. He didn’t pause or bristle. Indifferent, he continued to implant himself. Is this what I had been doing to others? What good could come of this type of transgression? Like a host organism recognizing a parasite, I panicked and pushed the hand out, bearing down until I could see its fingers withdraw and curl. I finished the drink, and declined his offer to buy me another. Someone brought hot bagels into the bar. He ate happily while I hydrated, aghast. I told him I felt the hand, and he acted confused. But a flicker beneath his expression, a lifted lip and breath of a smile, confirmed excitement. He had intended to make contact, to disturb. I let it go. I knew he would deny it. He might even flip the conflict, say that I set the trap or dreamed of some ghostly clutch.

Years later, I read online public letters by distraught students who complained of his bizarre demand for emotional vulnerability in his classes. Each recalled feeling threatened when expressing themselves around him, a trace fear of entrapment they couldn’t explain. Only after the dean asked him to leave his post did I understand others could feel this type of violation. An attack that had no name. We have invisible barriers for a reason. I saved myself when I learned to stop these casual abductions but I shudder at how long I spent confusing them with love.

Suzanna Clores

Suzanne Clores’s work has appeared in The New York Times, Elle, Salon, The Rumpus, Hypertext, and has aired on NPR. She is the author of Memoirs of a Spiritual Outsider, the creator of The Extraordinary Project Podcast, and the recipient of grants from the Illinois Arts Council. She lives in Chicago.