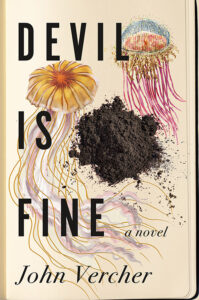

Hannah Grieco, editor-in-chief of the ASP Bulletin, interviews author John Vercher about his new novel Devil is Fine, from Celadon Books.

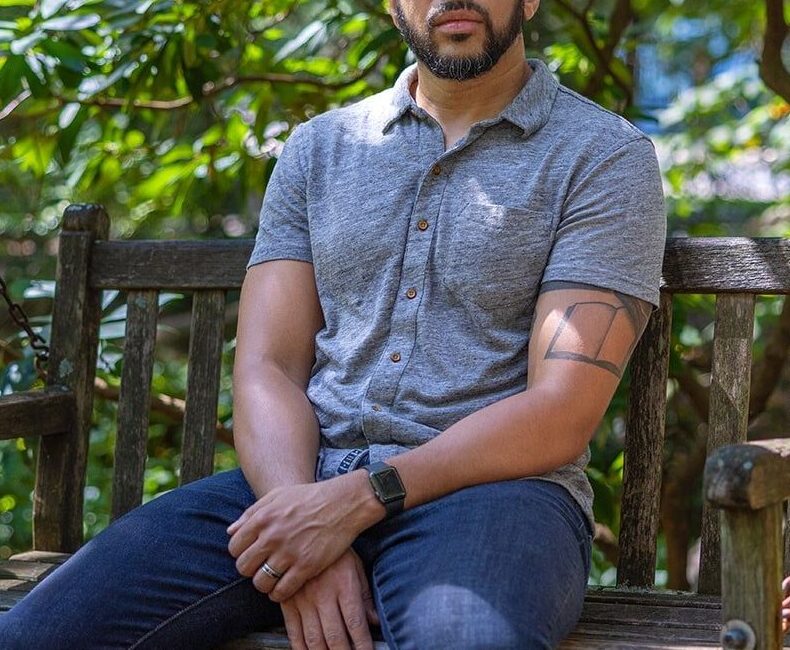

I was introduced to John Vercher’s writing in my MFA program at Randolph College, where I also received the enormous gift of his mentorship. His novels are visceral, immediate, and profoundly honest. They’re generous in both vulnerability and humor, much like their author.

Vercher’s newest novel, Devil is Fine, is out now from Celadon Books, and it does not disappoint. Once again—we are offered frank reflection, propulsive action, and humor in the face of life’s weight. National Book Award winner Jason Mott describes Devil is Fine as “part meditation, part fever dream, and part high-wire act that, somehow, Vercher executes flawlessly.”

It was an absolute joy to have the opportunity to interview my former mentor for The ASP Bulletin!

Hannah Grieco: Tell us about Devil is Fine!

John Vercher: I believe the maxim that once the book has left your hands, it belongs to the reader, so I’ll tell you what I think it is. I think Devil Is Fine is a book about being a father and a son, the legacies and the traumas we inherit, and about how the world sees us shapes how we see ourselves, told through the lens of humor, empathy, and a little surrealism.

HG: This book is deeply personal and immersive. I never assume any work of fiction to be rooted in its author's actual life—but I can't help but be curious about how being a father influenced your process. Can you talk about that a little?

JV: I’m not sure that I could have written this book without having been a father, though much of this revolves around the experiences of being a son as well. While it’s not autofiction, it’s safe to say I poured a good deal of my fears and doubts into it, as well as my joys in being both child and parent.

HG: From one parent writer to another: How do you write about the nightmare of losing a child? What does it take to put pen to page and write that story?

JV: Not that it was so long ago, but I remember the first day at home with my sons after they closed the schools because of COVID, when everything was so unknown. I was making their breakfast and was overwhelmed by this sense of panic because a question kept bouncing around my already anxiety-addled brain: What if this is it? What if this is the virus they’ve always warned us about? How do I explain to my children? How do I watch it take them? That fear had such a specific feeling, one that I’ve never forgotten. Writing was one of the few ways I could manage that feeling.

HG: Again, from one parent writer to another...and also from mentee to mentor: How do you come back to real life after writing that story? How do you return to actual fatherhood, unscarred?

JV: Like the narrator in my book, I’ve always been good at (sometimes to my detriment) compartmentalizing. That said, this book, while dealing with heavy subjects, had the opposite effect of scarring. I got to exercise some levity in the face of terrible things, something I also do in real life, also sometimes to my detriment and certainly to the annoyance of others. I wrote toward a possibility of hope because it feels like the world wants to take that from us by the minute.

HG: I think friendships are the hardest relationships to write. And your narrator basically learns to make friends in this book! Why did you choose to make these friendships such a central part of his story? Why not a romantic relationship, which probably would have been easier to write?

JV: As I get older, I’m increasingly interested in the dynamics of friendships—what gets them started, what makes them last, what causes them to end. That curiosity rises, I think, out of what I’ve found to be a winnowing of friendships over the years, not in quality, but in quantity. I saw that as sort of a natural progression, but when the pandemic hit, I was already working from home, and my isolation from others increased, and my anxiety struggles with it. I learned that perhaps that progression wasn’t so natural after all, so the formation of friendships has become an area of exploration for me.

HG: You and I share a love of Chet'la Sebree's poetry. What compelled you to quote her, and this particular passage, in your epigraph?

JV: Field Study is a top five all time book for me. There were several instances while reading where I had to set the book down and just—process. It’s one of those books that made me feel seen and understood at levels I didn’t know I was seeking understanding. Because Devil is about uncovering wounds that have barely or haven’t healed, because it’s about legacies we cannot escape, it felt as if our books were in conversation, and I was so honored when she agreed to lend me her words.

HG: What was your favorite scene to write in this book?

JV: Without giving too much away, the toad scene was a ridiculous amount of fun to write. For one, the experience was cathartic. I’ve had several jobs where I’ve wanted to quit and leave the bridge behind me smoldering but never did out of fear of professional retribution. But the most fun was writing from a place of ungoverned creativity—a place where I thought, “This is funny to me, and if it’s not to anyone else? Well, that’s okay.”

HG: What is something one of your characters did that surprised you? I know you wrote every word, of course, but still...I love those moments when our characters seem to come alive and do what they want

JV: I say this knowing full well how precious it sounds (at least to me) to talk about characters like they’re real people, but the aforementioned toad scene is that moment. I didn’t really know I was going to write that scene in that way until I came to that situation. The protagonist had been through so much up to that point that it would have been easy choice to have that scenario break him, but I was surprised at how good it felt to have him find this reservoir of strength he didn’t know he had.

HG: Because so many writers read our interviews, I’d love to dive briefly into craft. When you were revising, what's a memorable scene you took out? Why did you decide to cut it, and how did that help the story?

JV: Believe it or not, I didn’t cut any scenes. That’s not to say this hit the page fully baked, but my process—if you can call it that—is not to sit down at the laptop until I feel I’m in a place to write my best possible work. I do a lot of note taking in between those sessions, but I’ll sometimes go weeks at a time before I actually type anything.

HG: Could you briefly compare your process with this novel vs your other two? What has changed for you, as you've evolved as a writer?

JV: Not much has changed between the last novel and this one. The process between my first and second novel were markedly different, as my first novel was my MFA thesis. I followed a much more rigid schedule then as I had no choice. I was writing in the margins of a full-time job and caring for our very young children. With the second book, circumstances changed professionally, allowing me a bit more flexibility which allowed me to develop the process I now use. However, even that process is pretty fluid. I’m always curious about how others do it and seek other (better?) ways to write.

HG: What are some books you've recently read that knocked you on your ass?

JV: How much time have you got? OURS, by Phillip B. Williams, THE AMERICAN DAUGHTERS by Maurice Carlos Ruffin, BLACKASS by A. Igoni Barrett, GOD BLESS YOU, OTIS SPUNKMEYER by Joseph Earl Thomas, and HOUSE OF LEAVES by Mark Danielewski.

John Vercher

John Vercher lives in the Philadelphia region with his wife and two sons. He has a Bachelor’s in English from the University of Pittsburgh and an MFA in Creative Writing from the Mountainview Master of Fine Arts program. John serves as an Assistant Teaching Professor in the Department of English & Philosophy at Drexel University and was the inaugural Wilma Dykeman writer-in-residence at the University of North Carolina, Asheville. His debut novel, Three-Fifths, was named one of the best books of the year by the Chicago Tribune and Booklist. It was nominated for the Edgar and Strand Magazine Critics’ Awards for Best First Novel. His second novel, After the Lights Go Out, called “shrewd and explosive” by The New York Times, was named a Best Book of Summer 2022 by BookRiot and Publishers Weekly, and named a Booklist Editor’s Choice Best Book of 2022.