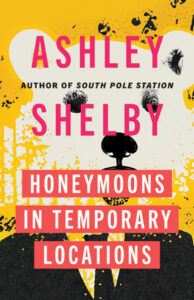

Ashley Shelby’s new collection, Honeymoons in Temporary Locations, eases the reader in through the retelling of a Melville story that was formerly about slavery and revolution. In Shelby’s re-imagining, the captives on the arctic boat are polar bears, and the expeditions that have come before the one we observe have been beset by madness - specifically, the boat’s crew becoming certain that the polar bears were not only aware in ways that replicated human awareness, but that they could and did talk.

This is the introduction of a theme that runs through experimental work, and appears later in clinical studies of a young woman who believes that birds speak to her, in tales of trees that move like Tolkien creations, and other anthropomorphisations we are to believe are either reality or a pathologized condition created by the grief of a world hurtling rapidly towards destruction.

“Solastalgia” runs through every creation in Shelby’s collection – a word coined by Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht, which means the grief caused by the rapid change of the world around us as climate disasters loom large. At first, it is an explanation. In later pages of the collection, it becomes something that drug companies latch onto as an illness and attempt to medicate away through a therapeutic dampening of empathy and a creation of psychopathy in its place.

But the overall thesis of the collection – mapping the contours of climate change in all who are affected by it, human, plant, and animal – is deepened greatly by the experimental forms that Shelby employs. In early pages, we have Craigslist ads that clue us in to the penalties for energy theft. We see restaurant menus that have nothing like the food we currently ingest on them, but rather strange combinations of hardy roots and plants. We are shown early stages of the creation of Climafeel, the drug that addresses the human reactions to climate change, as well as later advertisements where the creation of psychopathy has been softened to “Clekley’s Syndrome.” Peppered between these inventions are traditional stories where Shelby’s craft shines as brightly as in the more daring forms she sometimes employs.

“Muri,” the opening short story, was originally published as part of Radix Media’s brilliant Futures series, and received a Hugo nomination. When I read this story years ago, I was struck by the choice to include talking animals, something that is so hard to get away with outside of fairy tale retellings or the work of Murakami. I was delighted, as I dug into this collection, to see that Shelby kept up that daring choice. Everything has a voice in the world of Honeymoons in Temporary Locations. Birds sing, yes, but they also look at young women who can hear them and ask, over, and over, “Why?” In that one-word question, we see the destruction that humans have wrought as stewards of the Earth. I found it more moving than any long soliloquy that might come from a human mouth.

Experimental forms rarely get their due in modern fiction – many publishers believe they are “too risky,” or unnecessary. But the necessity of Shelby’s choices is obvious. In the section where we are presented with a future restaurant menu (the details of which, in more traditional fiction, might have been peppered through a narrative set in a restaurant), we are confronted which choice. The menu sits before us, seeming to say, “You have made your decisions and are left with these as your choices.” It is a stark statement that a phrase like, “He sat eating his dandelion flower risotto” could not convey.

In another cli-fi collection, we might understand that the “big heavy” is industry, the super-rich, or other forces beyond the everyday human’s control. Through the weaving of case studies, in-house drug briefings, and eventual ads for drugs, we understand still that the everyday human (and animal) is left to deal with the outcome of that which forces beyond their control has wrought, but here the real villain becomes those who will dull away the natural human reactions to the insanity of the dying world. As one character succinctly puts it, before going off on a diatribe about prayer in school and separating humans from God, ““It’s not like I’ve got a list of names. Powerful people. Like government people and rich people. They made this up. They want to make it into an epidemic so they can force medicine down our throats, subdue us, turn us into sheep.” While this character is off in his ultimate motivations, the moment of clarity he has about the “sickness” of solastalgia not being real is something that we the reader are already clear on.

Each one of Shelby’s experimental choices in the collection presents us with a new piece of the collage. Ultimately, these parts fit together to create a whole greater than themselves, and, like in any good piece of visual art, echo and complement each other. This cli-fi collection is vital, necessary, and prescient. It pushes the boundaries of what’s been done in the genre previously by both fracturing and fleshing out a world that we would do well to take heed of. Like all good cli-fi, I’m positive that this book will seem less like science fiction and more like realism in too short a time.

Alex DiFrancesco is the author of Transmutation, All City, and Breaking the Curse. Their work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Tin House, Brevity, and more. They are a 2022 recipient of The Ohio Arts Council's Individual Excellence Award, and the first transgender awards finalist in over 80 years of the Ohioana Book Awards.