It is a late Sunday afternoon in downtown Atlanta. The Conference on Myth, Fantasy, and Imagination, on the last of its four days, is taking a breather between the afternoon lectures and mealtime festivities. The conference is a serious affair and most people are here because of their work. Psychologists, art therapists, writers, scholars, health care specialists, and people for whom lifting the lid of the psyche is quest, a devotion, and for more than a few, a last resort. The book hall is largely text books. This is no Comicon. There is no pretending here to make-believe.

Tonight, after supper, the heavy hitters will take the stage. Poet Robert Bly, still going strong, along with Rumi translator and poet Coleman Barks, will square off tossing shards of verse at a very discerning audience who have learned the basics and are seeking something more. The two poets are, likewise, grizzled veterans who have been digging in these mines for a long time and bring to their presentation the freshness and ease that can only come from having touched every stepping stone along the way. Joined onstage by musicians playing cello, violin, and some type of zither, improvising along with their spoken verses to provide ambiance, the two masters are able to achieve the nearly impossible – to lift the audience out of time for a spell and show them a sacred hiding place, an open window, perhaps even a hint that a path might be found to some kind of salvation, or enlightenment, or peace.

Coleman Barks I knew only from his Rumi translations, but I wasn’t a stranger to Bly’s work, or his live reading personae. I greatly admired his book Iron John - a mythical travelogue through the primitive male psyche - and like-minded friends had given me audio books of the poet reading his work, which I listened to and savored on frequent cross-country drives.

Bly’s reading style is almost theatrical, enhanced by his strange other-worldly voice that is rather nasal and high pitched for a big fellow - a Minnesotan thing perhaps. It suits him. It softens the gravitas he brings to his delivery. He will repeat a line or couplet over again, when he wants the idea behind a phrase to sink in. He does this a lot. It’s like the singing of a chorus. This repetition also has a soothing hint of mesmerism to it. You don’t know when your feet have left the ground. That is the effect of working in parables, legends, myths, and allegories. He’ll give you a dramatic reading of a poem, then, like a good teacher, read it again with repetitions, walking you through meanings guiding you in deep. You thought you had a clue. You didn’t. Now you do.

A favorite poet of Bly’s is the Spaniard, Antonio Machado, whom Bly has been translating. He recites Machado in his entrancing style first.

The wind, one brilliant day, called

To my soul with an odor of jasmine.

“In return for my odor of jasmine,

I’d like all the odor of your roses.”

“I have no roses; all the flowers

in my garden are dead.”

“Well then, I’ll take the withered petals

and the yellow leaves and the waters of the fountain.”

The wind left. And I wept. And I said to myself:

“What have you done with the garden that was entrusted

to you?”

And Bly looks up at the audience, his full head of thick white hair long and deeply parted to the side, and reads each stanza again

The wind, one brilliant day, called

To my soul…

The wind, one brilliant day, called

To my soul with the odor of jasmine

“In return for my odor of jasmine,

I’d like all the odor of your roses.

In return for the odor of my jasmine,

I’d like all the odor of your Roses.”

People who think easily in metaphor can teleport to the heart of poems such as this. But sometimes this repetition technique can help us access unfamiliar material or discover something beneath the obvious meaning of words. The audience and he are in that place now, where personal truths float and swirl about the notion of the self. No secrets, no lies, no pretentions. Just being and time.

Coleman Barks and Bly then take turns reading and expounding, anecdotally blending their narratives, until the whole presentation is of a piece. Bly’s work fits seamlessly in with Bark’s Rumi translations and Rumi-inspired, more contemporary material. The well to which they return again and again is fathomless, the black water, deep down, unstirred for millennia.

The attendees at the Conference on Myth, Fantasy, and Imagination, are serious people. By participating here, they hope to get a little of themselves back from the banal lifelessness of our down-sliding culture. And that ultimately is a spiritual desire. If I have anything in common with these folks, it’s a need to re-acquire a sense of wonder, but with a mature longing for some kind of certainty. These notions aren’t necessarily contradictory, at least not in the re-prioritized world most attendees here would like to see come into being. The old hippie in me wanted to join right in. The writer in me, consequently, came away with a renewed sense of the marvelous, while at the same time longing for an assurance of sorts that my quest, or search for self, can proceed unmolested, and take me where it will.

By the afternoon before Bly and Barks do their thing, however, my brain is in dire need of a reset. I need a change of venue if only for a few hours. Almost everyone at the conference is eager to share whatever revelatory impressions of their own they are sorting through, but I now need other voices, or no voices at all.

The hotel itself is part of the problem. As magnificently huge as these corporate convention hotels can be, they often give me the creeps. Before long, the stark utilitarianism of these places starts to deaden the mind, and when the mind goes numb the soul withers. Is architecture dead? Overhead are thousands upon thousands of square feet of empty space. But it’s not empty. The same stale air is everywhere, as you can no longer open a window in a big hotel. I come to feel like I’m living on re-cycled carpet mites carried into my lungs by vacuum cleaner gas.

Strolling through the vaulted lobby, I realize that tomorrow this place won’t be filled with quirky artists, peace keepers, medicine women, and adventurers of mind and spirit, with their crazy hair and odd-looking clothes, carpet bags and fanny pouches. More likely, the hotel will be full of insurance salesmen, money managers, construction firms, and arms merchants. I’ve stood at a thousand modern metal bars like the one in the lobby here, struggling to find something interesting in whatever the flush-faced, bug-eyed business person next to me has to say, and I shudder with prickly pique.

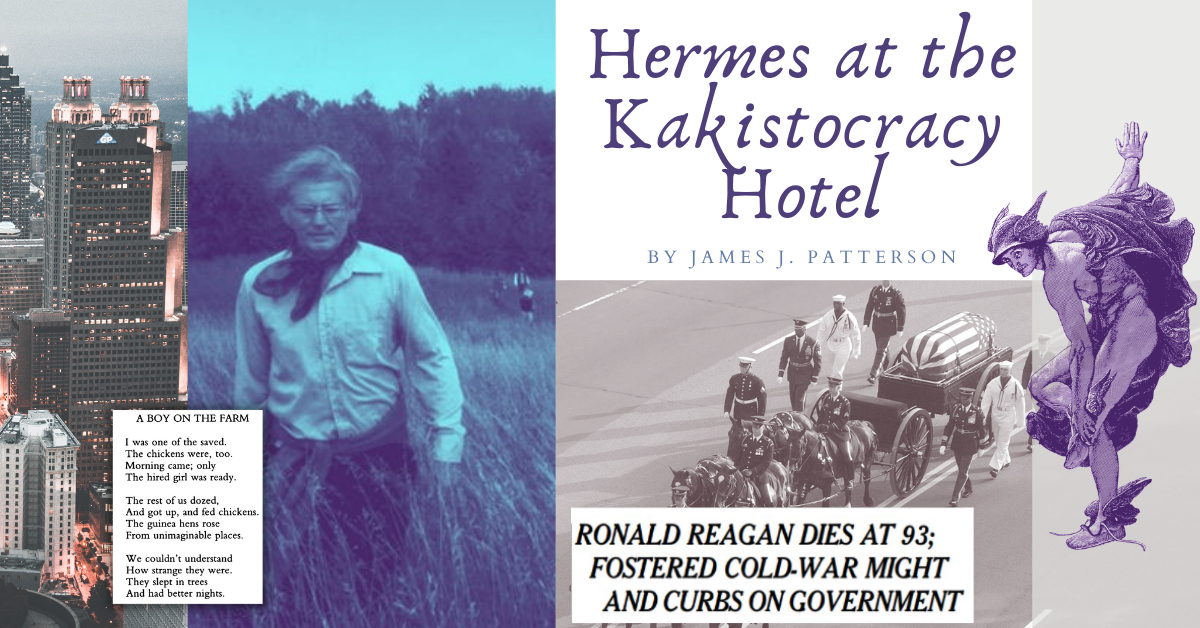

If a Kakistocracy is rule of a society by the worst men in it, then this is their hotel. The Kakistocracy Hotel.

Clearly, I need to get out of here. So, I decide to venture out on foot. I go back to the room and put on a sport coat, pull a tie I wore the night before over my head, leave my collar loose, and make for the exit. As I cross through the lobby toward the main entrance, a gust of fresh air from the revolving front doors pulls me from the place, past the valet parking attendants, greeters, doormen, and bell hops, all lurking about with nothing to do. The street is deserted.

Sunday.

Downtown.

Business district.

Right.

I have always been attracted to the esoteric, to the poetry and philosophy of mysticism, and to myth. This is why I’m here. Study is one way to open the doors of this arena, and though largely self-taught, I like to seek out living poets and scholars who know their turf better than I do. Sometimes those doors are shut to outside inquirers, but once in a while they open for us without any effort at all. Throughout my life, I’ve been lucky enough to glimpse what I will call an inkling of The Divine through chance encounters with strangers. One cannot, however orchestrate or pre-meditate, or conjure such encounters, a neat bit of synchronicity is required. The best one can do is expect the unexpected. So, naturally, when you least expect it, here it comes.

Standing on the sidewalk, breathing in the fumes of an early twenty-first century urban afternoon, I look right and left in search of a direction. Down the street, I spot the balcony of a restaurant, one story up, with an Old South filigree adorning the railings, homey and elegant, with lush thick vines hanging down. As I turn to make in that direction a very large black man steps deliberately in my path.

“I’ve got some bad news for you, little brother,” he says as he falls in with me and we walk together.

“Well break it to me gently, will ya? I’m a little short on coping skills today,” I smile, and by way of reassurance, I reach my hand up and grip his massive shoulder and give him a pat on the back.

He stops, I stop. He looks me deeply in the eyes.

“Ronald Reagan is dead.”

It might not have been the last thing I would have expected him so say, but it sure as hell wasn’t the first. He said it so gently, as though he thought I might fall to my knees in lamentation. I had to refrain myself from saying “Good riddance, now let’s get drunk!” I pause momentarily instead and take this guy in. He has stepped out of the world of strangers to give me the news. Why me, a middle-aged white guy in a jacket and tie, stepping out of a business person’s hotel? Did he think this was going to be bad news to me? He had no agenda that I could discern; there wasn’t a hint of hostility in his face or tone, and as has happened to me many times before, it was as if the wily Greek messenger god, Hermes, was speaking to me through this man. Come to think of it, my stranger on the boulevard and I might actually have been close in age. Nineteen-sixties people of all stripes called each other brother and sister back in the day. This man and I might have more shared ideas than a superficial glance at the two of us might detect. ‘Little brother.’ I liked that. He made it sound familial. I thought maybe it was.

I put my hand on his shoulder once more and say, “Well sir, I wouldn’t wish Alzheimer’s Disease on anybody, and I’ve known some dear ones afflicted with it, and it’s a big bad deal. But, to be honest, and forgive me if this sounds a little harsh, but in his case, I’m willing to make an exception. Welfare queens? Contras murdering socialists? Sympathy for abortion clinic bombers? Giant tax breaks for rich guys paid for by school kids, teachers, the mentally ill, wounded soldiers? I gotta tell ya big brother, I ain’t gonna miss’m.”

We continue on for a bit in silence, our hands on each other’s shoulder, like brothers, actually, the silence revealing a thousand cuts each.

“They said he didn’t remember being president,” the man said as we continued on down the street. We stopped and looked at the sky.

“Imagine that.”

“Imagine that.”

My father loved Reagan for cutting his taxes and could have cared less about the details. There were a lot of folks like my father. Reagan was their revenge on liberals whom they called “do-gooders,” like doing good was a loathsome betrayal of their greedy creed. They sincerely believed these “do-gooders” had robbed them of their discretionary income, only to give it away to losers and ne’er-do-wells who quite simply didn’t deserve it. But my parents’ generation had a lot more in common with the late President than mere fiscal hoarding, and some sophomoric rationale against accepting the responsibilities of wealth and its meaning to our culture and community well-being.

I remembered sitting at another Kakistocracy Hotel in Washington, D.C., shortly after Reagan’s reelection in 1984. At the table behind me a middle-aged black man was interviewing a recent college graduate, a young black woman, for a job in the administration. I overheard her come right out and ask him about the religious right, the saber-rattling, the welfare queens, and I can still hear him answer, “It is what it is. But if you want a job here then you’ll have to set all that aside.” I still shudder.

The Reagan generation was born into a world where electricity, urban plumbing, and automobiles were new or not yet extant. There wasn’t any radio, let alone television. My parents, both from small towns, truly believed that the world was so big you couldn’t pollute it. Reagan himself believed that smoke went up the chimney and then simply disappeared. The Greatest Generation? That generation tried to destroy the world over and over again, with genocide, then with atomic weapons, then with chemicals. They stopped short from killing us all, or merely were forced to hit the brakes momentarily, thereby prolonging the agony of self- destruction, and we call them great for it. Not so great from where I sit. I guess the implication is that a great many white people in WWII had to drop everything for a number of years, perhaps for a generation, and put themselves in harm’s way to get rid of Hitler and Tojo. But Hitler and Tojo were of that same generation too. How great is that? To me this greatest generation pablum represents a baffling type of hubris I can’t get my head around.

My Hermes on the street corner then wondered, “If someone could have sat by Reagan’s bed and told him what he had done, what might he have thought?”

Hmm.

We stood there, near the door to the restaurant with the appealing southern balcony, for several more minutes until we had concluded our conversation. We shook hands, concluding with a familial shoulder bump and hand clasp, and wished each other well. I could tell we were both wondering if we could, or even should, carry on. But that wasn’t the thing to do. He crossed the street. I went inside.

The wind left. And I wept.

The wind left. And I wept. And I said to myself:

“What have you done with the garden that was entrusted

to you?”

Myth, Fantasy, and Imagination, indeed.

The steak was delicious.

James J. Patterson

James J. Patterson was born in Washington, DC, five days before Nixon’s infamous “Checkers Speech.” He’s been lurking about in what he calls “The Capital of the Empire” ever since. As “Jimmy Pheromone” he crisscrossed north America 200 nights a year, writing and performing songs with the satirical art-folk duo, The Pheromones, playing what they called “Pop-Relevant Cabaret.” The ‘Mones were famous the world over for songs such as Yuppie Drone, Grace In The World, This Speech Is Free, and The Galactic Funny Farm. Patterson was the founder and publisher of SportsFan Magazine for ten years, reporting on and fighting for the rights of sports fans everywhere. Today he’s that friendly fellow sitting next to you on the subway, or at the ball game, or by the bar, ready to strike up a conversation. He wants to hear a story. Tell him a good one. He might just write it down.