WHETHER YOU LOVE IT OR LOATHE IT, there’s no denying that the holiday party season is all-consuming. Hosts everywhere order mistletoe, peruse catering menus, and search for just the right poet to read her work at their swank event.

What’s that, you say? Never heard of that last one? Indeed, of all your artist friends, a poet pal might be last one you’d think to ask to recite a few pieces at your holiday shindig. Musicians of all stripes are pressed into service this time of year, lending their flutes, guitars, or voices to the general mood of conviviality. A brave host with a nice wooden floor might even invite a ballet dancer to trot out the Sugar Plum Fairy solo. But I am here to tell you that poets, too, can be invited to “perform” at this time of year.

So here’s some advice: If you’re a host, don’t ask. And poets, if you do receive the call, don’t do it. Learn from my mistakes.

I was a naive young sprig of a poet when I first received such an invitation. My first book was just out, and a wealthy friend who fancied herself a kind of grand dame of the arts world wanted to turn her holiday party into, as she put “a real old-school French-style salon.” (I hold this woman responsible for the fact that, ever since, whenever anyone suggests holding a salon, my eyelid starts to twitch like Clouseau’s Inspector Dreyfus. But I digress.) Her plan was to scatter artists of various stripes throughout the main floor of her house, so that guests could sample a little original music here, a little live-action painting there, and then me, reading my introspective, coming-of-age poems.

“For maybe ten or fifteen minutes,” she said. “You’re really a guest, of course.” Translation: You’re not getting paid for my little experiment in entertaining, but you can drink and eat your fee. She plunked me in a chair in her den and let me go to it.

When I began reading there were perhaps ten people in the room. I started with a short, funny poem. They laughed, then half of them left. As I commenced my second, more serious piece, the other half slowly drifted out. I closed my book, and headed to the bar for a much-needed drink.

“No, you’re supposed to keep going,” my hostess said, accosting me in the hallway. “People will find you.”

I pointed out that all such people were either rocking out in the music room or, from the smell of it, getting stoned with the painter. She sighed a deep sigh, and I toddled off to get drunk. The food, of course, was distinctly un-French, and lousy.

You’d think I’d have learned my lesson. But a few years later, I was invited, along with a few other poets, to read my work in a new downtown shopping mall during the holiday season. The enterprising young real estate mogul who built it came up with this clever notion. Folding chairs and a podium were set out in the mall’s main hall, the idea being that exhausted shoppers might sit and refresh themselves with a few minutes of verse before going forth to spend some more.

The flaws in this idea were apparent by the time the second poet got up to read. No one sat, but a passing folks did say, quite loudly, “What the hell?” or some variation of that sentiment. Then the heckling began. Fortunately for me, we were reading in alphabetical order, and chaos descended long before I was supposed to take the stage. I slipped out quietly, vowing, never again.

So of course, it happened again — but in my defense, this one snuck up on me. My husband and I were invited to a New Year’s Day party at the home of a couple we’d just met. Both are professional, performing musicians, and therefore, one would think, too wise for such shenanigans. One would be wrong.

The food was terrific, the wine superb, and the festivities had reached their height when the male half of the hosting team decided it was time for his guests to hear some poetry. He took me aside, asked if I would recite something from my most recent book.

“Sorry, I don’t have anything memorized,” I lied.

“No problem!” He replied. “I’ve got your book right here.”

Before I could stop him, he was shuttling his guests into the house’s small front room, telling them they were in for a real treat. He pressed me into a corner between a window and the fireplace, where small flames were giving off what seemed an inordinate amount of heat. In my wool dress and tights, I was sweating before he put the book in my hands. I flashed distress signals to my husband with my eyes. He slipped up to me with a strong drink.

“Give ‘em one good one and get it over with,” he advised.

I decided to take his advice. But first, I leaned over and opened the window about two inches. A burst of very cold air did just a little to relieve my discomfort. OK, I thought, I can do this.

A few of the guests slipped out of the room and back to the food almost as soon as I started. I envied them. Ever the pro, I raised my voice a little to be heard over their chatter when I heard another, less familiar noise – a kind of crackling, growing louder and louder, followed by what sounded like a small bomb going off. Smoke filled the room.

“Oh, my god,” somebody said. “The house is on fire!”

“Don’t be silly,” our host responded. “It’s just an old fireplace. Keep going, Rose!”

Another exploding sound sent us all running outside. Above us, flames were leaping out of the chimney.

Someone called 911. Some other enterprising soul ran back inside to dump scoops of flour onto the flames. (Better than water, he told us. Who knew?) As the fire trucks pulled up, our host turned to me.

“This is your fault,” he said. “It was the breeze from the window that started this.”

“But that’s not possible.”

“Of course it is. It’s an old house. You should have known better. You opened that window.”

“But, but…”

By now, my husband was at my side with our coats, pulling me toward our car. But my erstwhile fan pointed to me, and announced to the rushing firemen, “It’s her fault! She opened a window!”

One of them stopped to take this in.

“Sir,” he said, “When was the last time you had your chimney cleaned?”

The answer, of course, was never.

The new friendship took a hit, but the house, at least, survived. And now I have one excellent excuse at the ready, whenever someone asks me to read my poetry at their holiday party: My work will set your house on fire.

Rose Solari

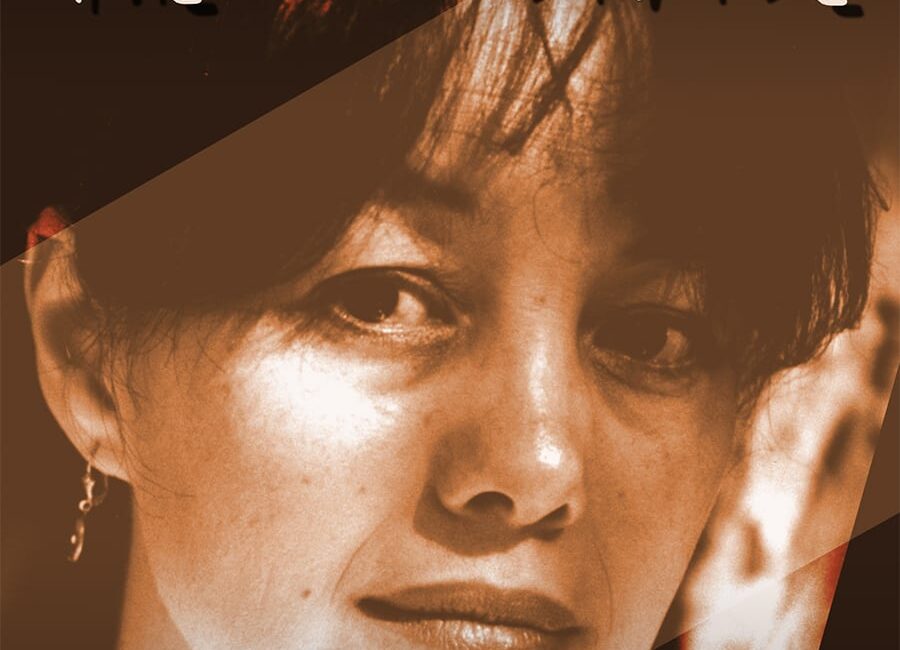

Rose Solari is the author of three full-length collections of poetry, The Last Girl, Orpheus in the Park, and Difficult Weather(re-issued by ASP in 2014); the one-act play, Looking for Guenevere; and the novel, A Secret Woman. She has lectured and taught writing workshops at many institutions, including the University of Maryland, St. John’s College, Annapolis, The Jung Society of Washington, and the Centre for Creative Writing at Oxford University’s Kellogg College in Oxford, England. Her work as a journalist includes numerous free lance assignments, as well as positions as staff writer and editor for SportsFan Magazine and Common Boundary Magazine. Her awards include the Randall Jarrell Poetry Prize, The Columbia Book Award, and an EMMA for excellence in journalism. She is currently a member of the Advisory Panel for the Centre for Creative Writing at Oxford University’s Kellogg College.

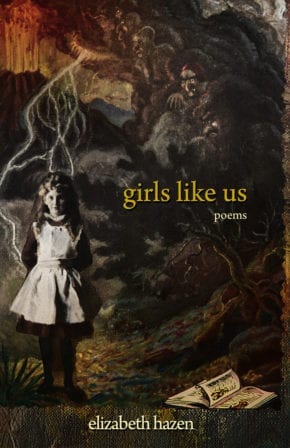

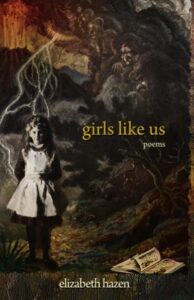

Girls Like Us is packed with fierce, eloquent, and deeply intelligent poetry focused on female identity and the contradictory personas women are expected to embody. The women in these poems sometimes fear and sometimes knowingly provoke the male gaze. At times, they try to reconcile themselves to the violence that such attentions may bring; at others, they actively defy it. Hazen’s insights into the conflict between desire and wholeness, between self and self-destruction, are harrowing and wise. The predicaments confronted in Girls Like Us are age-old and universal—but in our current era, Hazen’s work has a particular weight, power, and value.

Girls Like Us is packed with fierce, eloquent, and deeply intelligent poetry focused on female identity and the contradictory personas women are expected to embody. The women in these poems sometimes fear and sometimes knowingly provoke the male gaze. At times, they try to reconcile themselves to the violence that such attentions may bring; at others, they actively defy it. Hazen’s insights into the conflict between desire and wholeness, between self and self-destruction, are harrowing and wise. The predicaments confronted in Girls Like Us are age-old and universal—but in our current era, Hazen’s work has a particular weight, power, and value.