Mark A. Pritchard grew up in the New Forest, Southern England, a village with more sheep than people. He is the eldest of four siblings, whom he assures are recovering well. Mark holds a degree in drama from King Alfred’s College, Winchester. Tired of suffering Mark’s essays, the Head of Drama suggested he try a screen play as his dissertation. Words magically ceased to be mortal enemies and he has been captivated by story telling ever since. Rose Solari discovered him at the Oxford Literary ‘Fringe Festival’ in 2008 reading from his then work in progress, Billy Christmas. Mark lives in Oxford where he writes, acts, and patronizes the better pubs. His daughter is now old enough to despair in public!

ASP: For those who know nothing about Billy Christmas, could you summarize the basic idea in a paragraph or two?

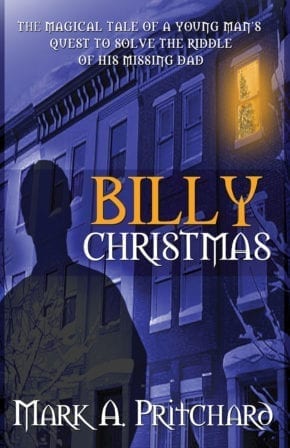

Mark A. Pritchard: Billy faces the first Christmas since his father vanished, without any explanation, the previous Christmas Day. He comes into possession of a magical Christmas tree which offers him a wish in return for the completion of twelve tasks. Each task is represented by a decoration (or ornament if you’re in [the US]!) and Billy takes them from the tree each night after midnight. However, the tasks spiral into dangerous territory, releasing unseen enemies and forcing Billy into the unknown to try to recover his father.

"I do chuckle when adults look and me with surprise and announce. “Mark, I loved it. It’s just like a real book!” Perhaps they were expecting a battered cod?"

ASP: What brought you to write the story of Billy Christmas?

MP: I’d been chasing an idea for a novel for some time. When you’re starting out you tend to seize on ideas which are really not much more than scenes. A novel needs an idea with legs!

ASP: You being a UK native, would you say BC has a distinctly British feel?

MP: That’s a hard one to answer as a native. Rose Solari and I mulled over whether the novel would serve readers better in US English, where Billy is published, or UK English where it is set; we went with the latter. I think that finally planted the sense of tone. The Oxford scholar, Diarmaid MacCulloch, was kind enough to compare the book to novels by Alan Garner, which I think probably settles that! Now I’m writing for the screen, particularly in science fiction, I find I’m writing much more Mid-Atlantic dialogue, which I find interesting and unexpected.

ASP: The description of BC on the ASP website reads “Billy Christmas is a boy with a man’s problems.”

Is this accurate? What does it mean to be a boy with man’s problems?

MP: Sometimes you need to be outside a thing to sum it up well, or see something quintessential about it. Alan Squire have a knack for doing this really well – and it’s not an easy. If I were to tweak this phrase I’d simply [say] that Billy has to struggle with challenges beyond his years. I’m not explicit, nor would I wish to be, about what a man’s problems might be – but if the reader finds something true in that, I’d be flattered.

ASP: Could you explain the concept of the 12 tasks in BC and where that idea came from?

MP: The original idea came when a roommate spurred me on, to enter a writing competition. When the idea landed I knew it was expansive enough to sustain over a book. That structure was a gift for a debut novel, which mentally are monumental efforts. For me to literally complete Billy’s tasks, allowed me to see the book emerge and solidify in a way previous attempts simply had not.

ASP: Who do you envision to be the audience for BC?

MP: I read Stephen King when I was nine years old. I believe young audiences should be largely self-selecting in judging what is right for them. Almost all are perfectly capable of closing books which take them to places they’re not prepared for. Parents, however, are a different matter. For sensitive parents I explain that there are scary themes within Billy Christmas, but if their child has read the final Harry Potter, then there is nothing they need worry about.

ASP: What do you want young adults who read the book to take away from it?

MP: That’s none of my business. The contract between writer and book, and reader and book, are two wildly different matters.

ASP: What do you want adults or parents who read the books to take away from it?

MP: Largely the same answer as above. However, I’ll add that I do chuckle when adults look and me with surprise and announce. “Mark, I loved it. It’s just like a real book!” Perhaps they were expecting a battered cod?

Billy Christmas is a boy with a man’s problems. Since his father disappeared mysteriously last Christmas, Billy’s mom has withdrawn into her grief, neglecting him and everything else. Now, in addition to his schoolwork, Billy must also keep the household running for both of them, paying the bills from their ever-dwindling bank account. Meanwhile, his father’s departure has become the chief topic of conversation in the small town of Marlow, and most of Billy’s classmates either ignore or bully him. He relies on his best friend Katherine for strength, and on his own inner certainty that somewhere, somehow, his father is still alive and wants to come home. Then, twelve days before Christmas, Billy is given a magical challenge, a series of twelve difficult and dangerous tasks. If he completes them all, his dream of being reunited with his missing dad might come true.

This is a book destined to be battered, much thumbed, read and read again until its pages come loose. It will graduate into the packing crate going off to college, then to the shelves at home, because Pritchard treats his young audience with emotional and literary respect. Pritchard understands that children’s emotions are as genuine as those of their parents, dark and foreboding in places, but never without hope. — James Clark, writer and former Sunday Times journalist