SOME CALL SHANGHAI THE PEARL OF THE ORIENT. And, in many ways, it is—organic, iridescent, a nacreous gemstone wrapped around a suffering center stuffed into the belly button of China. Behind it, China’s umbilicus, the great Yangtze, crawls through the fat middle of the country all the way from Tibet. Shanghai is young as great cities go. A murky backwater for centuries, its origins as a cosmopolitan center are rooted in the 1843 Treaty of Nanjing and trade concessions won by the British in the ignominious Opium Wars which allowed British merchants to continue to pollute the Chinese populace with opium imported from India in the name of balancing trade. Shanghai, like Xiamen, Canton, Fuzhou and Ningbo, became a “treaty port” where foreign powers (the British and later the French and the Americans) were granted autonomous, self-governing settlements. Extraterritoriality— freedom from Chinese law and a great distance from their own—came with a license and licentiousness that lent Shanghai all the gravity of a frat party thrown in someone else’s house.

Fortunes were made there, and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the Manchu dynasty breathed its last, money poured into the city. It was the place for youngest sons to go to make a fortune; for adventuresome women to find freedom and a leg up, so to speak; for anyone fleeing from an unjust history or a sordid past to hide; for teachers and preachers in search of a flock. Righteous, avaricious, British, French, American, Russian, Indian, Japanese—the world, it seemed, swarmed to the muddy mouth of the Yangtze to mingle and mix with abandon in a wild, feeding frenzy. And while Chinese revolutionaries plotted and uprisings rose and fell, Shanghai real estate shot upwards in a rash of high-rise edifices with skyhigh prices.

In 1925 when my mother, Genie, a.k.a. Georgiana Mildred Hughes, moved to Shanghai at age four, the city was booming, divided up into a singsong of settlements belonging to multinational communities that had over the past eighty years developed their identities and expanded their reach. At the center of this universe was the Bund, a classy cummerbund of banks and trading houses situated at a bend in the Huangpu River on what was once a muddy towpath. Gateway to China via the sticky fingers of the British and American Concessions known collectively as the International Settlement, it was an imperious one-mile strip bounded in the north by Suzhou Creek and the Garden Bridge and in the south by Avenue Edward VII.

Symbols of status and wealth abounded on the Bund. Here rose the port city’s all-important Customs House with its grand clock, a replica of Big Ben sarcastically dubbed Big Ching; the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation building, home of the second largest banking institution in the world at the time; and the opulent art deco Cathay Hotel, erected by millionaire trader Sir Victor Sassoon, a testament to the rewards of international drug sales. Beyond this impressive sweep of powerhouses stretched an elitist world of private clubs, expensive shops and hotels where wealth was flaunted and the city’s first park was closed to dogs, bicycles, and the Chinese.

This is the Shanghai my mother remembered—the Shanghai she called home until 1937. It was a dazzling world to child and adult, alike, a world filled with chauffeurs, dressmakers, pastries, parties, movies, movie stars, and electrifying sporting events, but there was also poverty and a prejudice to which my mother, daughter of a Welsh professor of English Literature and a Japanese actress, was hardly immune.

Mother lived on Avenue de Roi Albert in the French Concession. At the time, the French Concession was the place to be. Even the wealthy Taipans, flush from their business dealings in the banks and “hongs”—the trading companies on Nanjing Road—made their homes in the French Concession, surrounding themselves with thick walls, ample gardens and armies of servants. A bohemian center that drew artists, entertainers and their well-heeled patrons, the French Concession also supported a refugee population that included White Russians, European Jews and others down on their luck or quite literally at the end of their rope. To the north, in the International Settlement, activity centered around Nanjing and Bubbling Well Roads, the large east-west artery that extended from the Bund to Bubbling Well Cemetery with the fashionable and much frequented racetrack in between. But it was Avenue Joffre, sometimes called “Little Russia” because of its large Slavic population that was the city’s emotional center. Just south of Avenue Edward VII, it was a welter of Mom & Pop businesses where elegant but impoverished immigrants harnessed their courtly credentials by serving up fashion to the local hoi polloi in a struggle to make ends meet. The public schools were crowded with the children of these parents in distress. Edith, a Czechoslovakian girl and contemporary of my mother’s, whose family were among the 25,000 European Jews who found asylum in Shanghai, remembers the bakery her parents opened on Edinburough Road. Edith’s family was relocated in 1943, when the Japanese took over Shanghai, to the Jewish ghetto in Hongkou, in the old American Settlement, where they were confined along with thousands of other Jews until 1945 when Chiang Kaishek and the Kuomintang took back the city.

Dire as these circumstances were, they weren’t as bad as the situation for the indigenous population and for the thousands of Chinese refugees who had flocked to Shanghai’s well-fortified western enclaves in search of protection from a merry-go-round of political skirmishes and rebellions. They lived in abject poverty, supplying the city’s colonial keepers and their Chinese partners with an exploitable, expendable and seemingly endless source of manual labor and a market for their drugs. At one time there were close to 1500 opium dens in Shanghai and over 50 shops that peddled it openly. Gangsters like “Big Eared” Du Yuesheng capitalized on this depravity, making financial killings in opium, prostitution and labor racketeering and finding acceptance and even respectability in a governing body with similar values. Shanghai was a desperate place.

Children, like many of my mother’s cousins and friends, fell prey to illnesses and epidemics: malaria, influenza, pleurisy, leukemia. Adults fell prey to other maladies like profligacy and the temptations of alcohol, drugs and gambling. Factory workers died of lead and mercury poisoning; porters and rickshaw drivers dropped dead in the streets; beggars starved; and brothels filled up with young women with no other means of support. The destitute were ignored. It’s no wonder that the push for a new order took hold and that when the occupying Japanese were finally ousted in 1945, it was the Red Chinese who eventually took control.

Today, after decades of social penance under the scouring influence of communism, Shanghai has resumed its capitalistic course, this time with Beijing’s blessing. The French Concession is again the place to be—hallowed, in a way, by its significance as a cradle of communism. Radical young intellectuals were part of the scene in the ‘20s and today you can visit the site of the first National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party at 76 Xingye Lu, as well as the former residences of early revolutionary Sun Yatsen and Zhou Enlai, first premier of the People’s Republic of China.

In an irony that is impossible to miss, Huaihai Lu (it used to be Avenue Joffre) has re-emerged as a key commercial strip, though the Old World gentility has been all but expunged and replaced with super-sized fashion franchises brokering brands to the terminally trendy. Side streets like Shaanxi Nanlu (old Avenue de Roi Albert), and neighboring Maoming Nanlu and Changshu Lu feature, as they did so many years ago, a host of little shoe stores and dress shops. New cafés, restaurants and nightclubs beckon. The often tree-lined streets still sport a continental color, and the concession-era ambiance of backstreets dotted with small businesses, boutiques and art galleries attract tourists and serve as an oddly welcome reminder that Shanghai, once the Paris of the East, is back in business.

Other old habits have resurfaced. Western visitors again gravitate toward the Bund with its antique symbols of European dominance and savvy developers have been happy to comply, dusting off colonial haunts and reframing them for a new generation of devotees. The Peace Hotel, which in its former Cathay Hotel incarnation was home away from home to such notables as Charlie Chaplin, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Coward, still draws sentimental admirers with romantic notions of Shanghai in its decadent heyday and Nanjing Lu and Nanjing Xilu (once Nanjing and Bubbling Well Roads) with their big department stores, museums, top-of-the-line hotels and high-end shopping are as popular as ever with the local and international set.

But for a look at old Shanghai, the crowded lanes and alleys of Nan Shi are the traveler’s best bet. This is the Old Town, where the Chinese first settled in a walled encampment constructed to deter Japanese pirates. Cramped quarters, crowded lanes, back alleys strung with laundry and a cacophonous and odiferous tangle of sights, sounds and smells suggest the heady combination of sensory stimulation that surrounded residents of old Shanghai. Here you’ll find recently restored neighborhoods like the area around Fangang Zhonglu and temples and tenements and street vendors selling the same snacks—dumplings (xiaolongbao), baked sweet potato, shaved ice and syrup (bingsha) and roasted chestnuts (in winter)—that tempted children back in the ‘20s and ‘30s when my mother was a girl.

But Shanghai also has a new face. Developed by the Chinese government in an attempt to make the port city the financial capital of Asia, the Pudong New Area on the eastern bank of the Huangpu River has sprouted from the bog that in the past served alternately as a farmland supplying pigs and vegetables to Shanghai and a storage area where the port’s godowns (warehouses) and compradors (buyers) shifted and sorted the sources of trading house fortunes. In 1990, when Shanghai became an autonomous municipality, Pudong was identified as a special economic zone. Today, clearly the result of a great deal of attention and investment by the central government, it has evolved into a kind of Buck Rogers-George Jetson City of the Future complete with two billion dollar airport, superlong suspension bridges, MagLev train service and soaring superstructures that vie with other Asian skyscrapers for the title of tallest. At eighty-eight stories, the observation deck of the Jinmao Tower, the fifth tallest building in the world, offers the best views of modern Shanghai. The Shanghai Municipal Historical Museum in the basement of the shocking-pink, scifi-style Oriental Pearl Tower—the world’s third tallest tower— provides an interesting glimpse of Shanghai’s past. Both structures are located in the Liujiazui Finance and Trade Zone, home to China’s stock market and headquarters for foreign banks. Pudong, which is actually larger than urban Shanghai, is mainly a place for business, though it also home to the city’s most modern hotels. The Park Hyatt, which occupies the fiftythird to eighty-seventh floors of the edifice, is certainly one of the most spectacular places to stay in the city. With its international investors, tax-free foreign trade zone, hi-tech zone, export and processing zone, Pudong is a celebration of capitalism that puts other centers of commerce to shame.

In fact the new Shanghai has a great deal in common with the old. The communist regime was particularly hard on Shanghai, believing the western loyalties and bourgeois values it promoted were especially pernicious. Maybe they were on to something. The beggars are back. So are the expats, the drugs, the sex, the shopping and the real estate boom. The Chinese would say that places have personality, an energy and a spirit that is the product of their geography. If this is the case, Shanghai will always be the head of the Yangtze dragon: powerful, irrepressible, optimistic, wealthy, ambitious, dangerous. Oh yes, and a little vain.

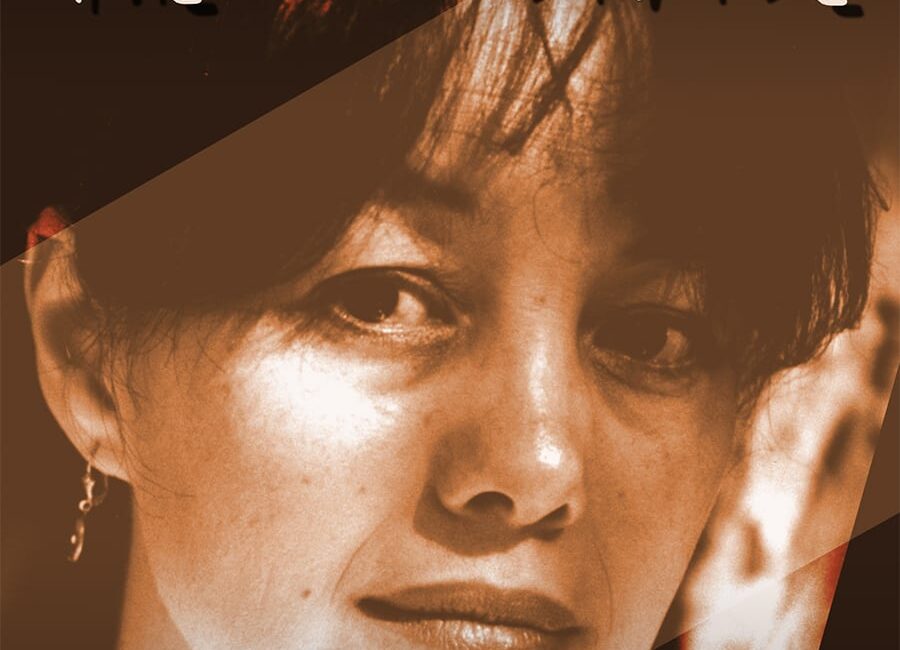

Navigating the Divide is a career-spanning, multi-genre collection from the award-winning indie literature legend, Linda Watanabe McFerrin. In poetry, essays, and fiction that are often profoundly personal and astoundingly surreal, this world traveler and literary explorer busts walls, erects bridges, and ambiguates genre. This multi-faceted collection sets out to attempt its namesake, to “navigate the divide” – between spiritual and physical, between thought and desire, between individual and collective.

Navigating the Divide is the third volume in ASP’s Legacy Series. This series is devoted to career-spanning collections from writers who meet the following three criteria: The majority of their books have been published by independent presses; they are active in more than one literary genre; and they are consistent and influential champions of the work of other writers, whether through publishing, reviewing, teaching, mentoring, or some combination of these.